Climate change constitutes one of the most pressing global challenges of our time. Its impacts fall disproportionately upon indigenous communities who have contributed least to its causes yet possess generations of adaptive knowledge (Dorji et al., 2024). Across Africa, dryland ecosystems cover 40% of the continent’s landmass and support nearly 50% of its population, making pastoral communities particularly vulnerable to climate variabilities (FAO, 2018). This blog draws on insights from my AFAS-funded fieldwork to examine how Indigenous Knowledge systems shape adaptation strategies among Maasai pastoralists in the Kitenden-Amboseli ecosystem, focusing on indigenous grass reserves as a Nature-based Solution for climate adaptation.

The research journey

I am a Master’s student in ‘Culture and Environment in Africa’ at the University of Cologne. In 2025, I received the AFAS-DAAD grant for fieldwork, which brought me back to my community in Kenya. As a Maasai researcher from Kitenden, conducting fieldwork at home presented both unique opportunities and responsibilities: my positioning enabled access to governance processes that might remain opaque to external researchers, while maintaining dual accountability to academic rigour and community interests. I began with a question: why do functionally effective indigenous systems remain invisible within policy frameworks that claim to value locally-grounded approaches?

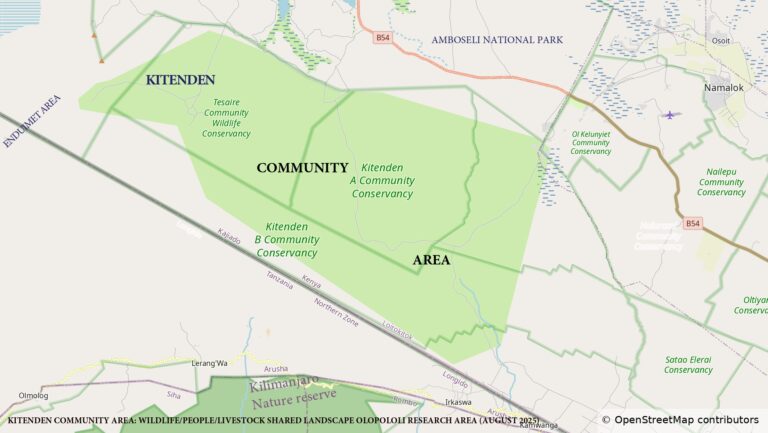

My research involved interviews with community elders (men and women) across villages in Kitenden, a community land area serving as a vital shared space for people-livestock-wildlife corridor connecting Amboseli National Park to Mount Kilimanjaro and Enduimet conservation area (Mwangi & Mbane, 2020). I found that olopololi[1]—a traditional grass reserve system—remains very much alive as both a geographical grass reserve, and sophisticated governance institution sustaining pastoral livelihoods across changing climatic conditions.

Source

OpenStreetMap: https://www.openstreetmap.org/#map=12/-2.7567/37.3039

What is olopololi?

Olopololi (plural: ilopololi) refers to designated grazing reserves that Maasai communities close to livestock during wet seasons to allow vegetation regeneration for dry-period use. The term derives from a-lili (to smell badly), marking that violators of reserve protocols ‘feed their stock on smelly grass’—pasture unsafe for livestock (Mol, 1978). Ol-opololi—literally ‘that which is set apart for feeding’—represents areas reserved for critical dry-season grazing (Western & Dunne, 1979). This semantic connection between social transgression and ecological degradation positions grass reserves as moral sites where collective principles determine resource access.

While Western and Dunne (1979) first documented these reserves, and BurnSilver et al. (2008) noted their continued ecological effects, systematic analysis of their governance remains limited. As one 70-year-old Maasai woman explained: ‘Olopololi comes from within us. It shows that we create olmanyara [environments] so that calves can graze on pasture that has not been depleted.’ Elders select sites based on landscape features: iyarat (geographical areas with water accumulation and fertile soils) and esanarua (land area retaining stagnant water) are preferred, while areas with poor grassland potential are avoided.

Governance that works

The Maasai of Kitenden manage olopololi through sophisticated institutional governance with defined rules, monitoring, and graduated sanctions. Access is regulated by councils of elders—both men and women with deep knowledge of livestock and pasture. Women typically oversee olale (reserves around homesteads), while men manage distant grazing areas. As an age-set chief explained, ‘In Maasai society, traditional chiefs formulate laws and determine fines for violations.’ Today, grazing committees enforce sanctions reaching 5,000 Kenyan shillings for unauthorized access.

This system aligns with Ostrom’s design principles for sustainable common-pool resource management (Mwangi & Ostrom, 2009): defined boundaries (marked by stripped tree bark or landscape features), collective choice arrangements (elder deliberations called enkiguena), monitoring (warriors and grazing committees), and graduated sanctions.

Olopololi serves functions beyond livestock management. One elder noted that wildlife do not deplete reserves like cattle, as they move linearly without uprooting grass. Ecological research confirms these reserves function as ‘fodder resources for livestock and wildlife, pollinator conservation areas, carbon sequestration sites, and nature-based restoration solutions’ (Hezron et al., 2024, p. 2). Fire management is also embedded: unused old grasslands (inkujit naatorokita) are burned before rains through a practice called impejot, reducing livestock disease while promoting regeneration.

The challenge: Land subdivision

Every interviewee expressed concern about olopololi’s future amid accelerating land subdivision. Historically, Maasai managed rangelands through communal systems enabling flexible governance. Colonial and post-independence interventions transformed this into individual titles through Group Ranch formation and subdivision (Galaty, 1994; Lesorogol, 2008), fragmenting landscapes that once supported coordinated management.

An 85-year-old woman articulated this tension: ‘If a person owns 21 acres, it becomes difficult to keep 200 cattle. How can such small land be divided to create olopololi? It is not possible.’ Ecological assessment shows 65% of Kitenden’s ground lacks herbaceous cover, accelerating after 2000—coinciding with subdivision (Mwangi & Mbane, 2020). Yet communities adapt: some pool individual parcels to reconstitute reserves; others uphold customary arrangements. Grazing committees now integrate scientific techniques like rotational grazing systems, blending customary and contemporary approaches.

Implications for science-policy-practice interfaces

My research speaks directly to AFAS’s focus on Science-Policy-Practice Interfaces (SPPI). Elders possess sophisticated ecological knowledge systematically excluded from conservation policy. As one observed, many ‘scientific innovations’ in conservation reproduce principles indigenous systems have sustained for generations. This paradox—functional effectiveness alongside policy marginalization—cannot be explained technically. If effectiveness determined recognition, grass reserves would be policy priorities.

Political ecology reveals this marginalization as structural, built into conservation science’s epistemic foundations and reproduced across colonial and post-colonial periods (Goldman, 2003; Robbins, 2012). Scientific knowledge overshadows indigenous knowledge at policy interfaces, reducing its perceived value (Tengö et al., 2017). Across East Africa, pastoral communities have experienced land dispossession under conservation regimes portraying pastoralism as environmentally degrading (Hughes, 2006). Recognizing olopololi as legitimate environmental governance—rather than ‘traditional practice’ needing modernization—would enable more equitable engagement between conservation institutions and pastoral communities.

[1] Italicised words represent Maa (Maasai) terms.

Looking forward

When I asked elders what they hoped this research would achieve, responses were consistent: recognition and respect for their knowledge systems. As one explained, ‘The power of your work is to reinforce that the Maasai should be given space to practice livestock keeping as they traditionally did.’

Grass reserves hold both memory and future. Examining how olopololi were historically organized, disrupted by external pressures, and sustained despite constraints offers critical insights for climate adaptation. As pastoral ecologist Gufu Oba noted, ‘Pastoralism will never disappear. Collapse and recovery will continue.’ The question remains whether policy frameworks will recognize what has long been present.

Acknowledgements

I thank the elders of Kitenden Conservancy for sharing their knowledge. This work was funded by the German Academic Exchange Service DAAD (through the Climate and Environment Centre ‘Future African Savannas’) from funds of the German Federal Foreign Office. I also thank my supervisors, Prof. Dr. Michael Bollig and Dr. Gerda Kuiper at the University of Cologne.

References

Photo credits

The Author took all the photos used in the blog.

Information about the author:

Saitabau Lulunken is a Maasai scholar from Kitenden in Kenya’s Amboseli region and a master’s student in ‘Culture and Environment in Africa’ at the University of Cologne. His AFAS-DAAD-funded research examines indigenous grass reserves as Nature-based Solutions for climate adaptation.

Contact: saitabaululunken[at]gmail.com