Introduction

Protected areas, often described as sanctuaries for biodiversity, are central pillars for global biodiversity conservation. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) defines them as “clearly defined geographical spaces, recognized, dedicated, and managed through legal or other effective means, to achieve the long-term conservation of nature with associated ecosystem services and cultural values” (Dudley, 2008, p8). Given this vital mission, the expansion of protected areas is both necessary and urgent. In response, 196 countries adopted the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework in 2019, setting a bold target to protect at least 30% of the Earth’s land and oceans by 2030.

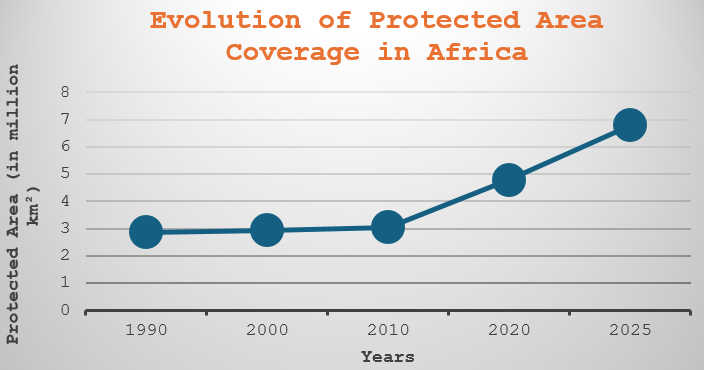

As illustrated in the graph below, Africa’s network of protected areas has expanded substantially. As of June 2025, the World Database on Protected Areas (WDPA) reports 8,948 formally registered sites covering 6,8 million km2, more than twice the coverage recorded in the 1990s (UNEP-WCMC and IUCN, 2025; World Bank, 2025).

Yet, despite this expansion, biodiversity across the continent continues to decline even within these protected areas (Natural History Museum, 2024). This paradox raises a fundamental question: how can species and ecosystems continue to vanish, even though conservation areas are expanding? In this blog, we explore some cases of biodiversity decline in West, East, and Central Africa; discuss two major underlying causes; and finally argue for a functional science-policy-practice interface to ensure more effective and impactful conservation outcomes.

A Snapshot of Africa’s Biodiversity Crisis

In West Africa, Nigeria stands out with 1,002 protected areas covering 126,735 km2, about 14% of its land (UNEP-WCMC and IUCN, 2025). Yet, the country faces a severe biodiversity crisis. In Gashaka-Gumti National Park, which houses Nigeria’s largest chimpanzee population, numbers have dropped by over 60% in two decades. Similarly, in Yankari Game Reserve, the elephant population has fallen from 500 in 2001 to fewer than 100 in 2023 (WCS, 2023). In East Africa, Kenya is famous for its breathtaking wildlife, whether you are in Tsavo, Maasai Mara, or Nairobi National Park. However, behind this fascinating beauty, a silent crisis is unfolding. Within four decades, Kenya has lost on average 68% of its wildlife numbers, and up to 88% for some species (Ogutu et al., 2016). At the heart of Africa lies the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), a global hotspot with immense biodiversity and one of the largest networks of protected areas on the continent covering 328,500 km2, about 14% of its land. Yet, DRC faces a grim reality: more than 390 of its species are classified as threatened by the IUCN, and all five of its World Heritage Sites are listed as World Heritage in Danger (Pélissier et al., 2018).

Two of the Key Drivers of Biodiversity Loss in Africa

While Africa’s biodiversity crisis is driven by multiple interconnected factors, below we explore two of them: funding and management deficiencies and interconnection with armed conflicts.

(1) Chronic Funding Shortages and Management Deficiencies. Financial shortfalls are pervasive in Africa. A 2018 study found that only 10 to 20% of African protected areas supporting lion populations meet the average financial requirements, with an annual deficit ranging from $0.9 to $2.1 billion (Lindsey et al., 2018). A similar study revealed that 78% of protected areas in 25 African countries face a $1.5 billion annual shortfall to meet the minimum requirements to stabilize elephant populations (Correa et al., 2024).

In today’s polycrisis world, the lack of adequate funding is like a drought that parches the roots of conservation efforts, leaving them withered and struggling to survive. Funding shortages are further exacerbated by some African national governments that appropriate part of the already limited funds secured by protected areas—reaping where they have not sown. These financial shortfalls trigger cascading ripple effects, reducing management effectiveness, sometimes to the point of systemic dysfunction, and intensifying conflicts with local communities. Consequently, many protected areas have been downgraded, downsized, and/or degazetted, while others persist only as “paper parks,” legally designated but functionally defunct.

(2) The Overlap between Conflict Zones and Biodiversity Hotspots. About 90% of major armed conflicts in Africa occur in countries with biodiversity hotspots, and over 80% take place directly within hotspots (Hanson et al., 2008). Another study, covering 3,585 protected areas across 51 African countries from 1946 to 2010, found that 71% of these areas had experienced armed conflicts in varying forms (Daskin & Pringle, 2018). This study also shows that just one year of armed conflict can push wildlife below sustainable levels. One of the striking examples is Kahuzi-Biega National Park, a UNESCO World Heritage site in the DRC, which between 1999 and 2000 lost 128 eastern lowland gorillas, a species that has since been reclassified from endangered to critically endangered (Simpson, 2024).

This overlap is largely driven by economic incentives: armed conflicts fuel illegal trade in natural resources, and the income generated sustains the conflicts. In the Congo Basin, Nellemann et al.(2015) found that the illegal trade in natural resources from gorilla habitats generated several hundred million dollars annually. This is similar to pangolin trafficking in Nigeria. These armed groups are well-structured networks, connected to local elites and global markets, making them difficult to dismantle.

A three-pillar solution: strengthening the science-policy-practice interface in African conservation.

Experts warn that Africa’s biodiversity crisis will persist unless decisive, evidence-based actions are taken. Too often, groundbreaking research remains unpublished, forgotten, or locked behind paywalls; policies are copy-pasted without being contextualized; and outdated practices are repeated on the ground.

For instance, the expansion of protected areas is frequently driven by global targets (e.g., the “30×30” initiative), rather than focusing on species-specific metrics. In Kenya, 70% of wildlife, including iconic species live outside protected zones (Ogutu et al., 2016). In DRC, only 20% of threatened amphibian and reptile species are within protected areas (Chifundera, 2019). The expansion of protected areas has become a symbolic gesture, creating an illusion of progress while masking inefficiencies on the ground.

A key step to turn the tide is to implement a science-policy-practice interface institution at both the continental and national levels. Each African country urgently needs a structured and functional approach to co-create knowledge and translate evidence into well-rounded policy and measurable actions. Such an interface would ensure research directly addresses policy gaps and practical challenges, policies are rooted in local data instead of being copied templates, and practices evolve through science-backed innovation securing, biodiversity and livelihoods.

Conclusion

We often attribute biodiversity loss to anthropogenic pressure, overlooking that protected areas exist precisely to counteract such pressure. Their true value is revealed under these high-pressure conditions. Instead of using anthropogenic pressure as a simplistic explanation, we must critically evaluate whether protected areas are effectively designed, managed, and supported to fulfill their mandate. Protected areas, like seeds, require more than mere designation; they need continuous investment, governance, and adaptive strategies to grow and thrive.

There is no universal blueprint for conservation success. Flexibility is the key, and the best decisions are those grounded in local evidence, backed by responsive policies, and embraced by local communities. Thus, we propose institutionalizing a functional science-policy-practice interface at both the continental and national levels. This interface would create a virtuous cycle where science informs policy, policy enables action on the ground and practice feeds back into research. Achieving this requires science-policy-practice architects, expert bridge-builders who can unite these disciplines. The challenge is immense, but the impact will be profound. Will you join us?

References

Information about the authors:

Jonathan Bachiseze Magala from DRC, is an AFAS Scholar of the 2nd master Cohort based at the Université Félix Houphouët-Boigny in Côte d’Ivoire.(a.jonathanbachiseze.m@gmail.com)

Kabir Adelakun Adekunle from Nigeria, is an AFAS Scholar of the 2nd master Cohort based at the Université Félix Houphouët-Boigny in Côte d’Ivoire.(kabiradelakun3@gmail.com)

Julius Toba Malika from Kenya, is an AFAS Scholar of the 2nd master Cohort based at the University of Nairobi in Kenya.

(julius.malika@students.uonbi.ac.ke / julius malika91@gmail.com)