When I arrived in Korhogo, northern Côte d’Ivoire, for my master’s fieldwork under the African Climate and Environment Center – Future African Savannas Programme (AFAS), I expected to study agroforestry diversity in typical savanna landscapes. In Côte d’Ivoire, Korhogo is considered one of the pioneering regions of agroforestry, a Nature-based Solution that integrates trees and crops on the same land to enhance biodiversity, improve soils, and strengthen resilience.

Instead, I was struck by the overwhelming presence of cashew trees (Anacardium occidentale), an exotic species originally from Brazil. This raised several questions: Why was this species introduced? Why did it expand so rapidly? And what sustainability lessons does this expansion offer for scientists, decision-makers, and practitioners? This piece combines insights from my fieldwork with existing literature.

Origins: Introducing Cashew to Northern Côte d’Ivoire

Cashew was introduced to Côte d’Ivoire in the 1960s through state-led reforestation programs aimed at halting desertification and controlling soil erosion in the arid northern savanna. Its resilience to drought and poor soils made it an ideal species for creating a natural barrier against the southward advance of the desert. Early results were encouraging, attracting continued government and donor support.

Transformation: From Restoration Crop to Cash Crop

In the 1970s, global demand for cashew began to rise, following advances in processing and increased awareness of its nutritional value. In the 1990s, prices had doubled, turning cashew into the most profitable crop in northern savanna zone of Côte d’Ivoire (Dugue et al., 2003).

By 2022, cashew covered 1.6 million hectares nationwide, supporting the livelihoods of about 1.5 million people, including around 500,000 smallholders (Mighty Earth et al., 2023). National production rose from 16,000 tonnes in 1994 to 1.2 million tonnes in 2023, representing 40% of global supply, with annual exports exceeding $800 million (World Bank, 2024). The northern regions, including Korhogo, are central to this boom.

Survey with 100 randomly selected agroforestry farmers in 10 Korhogo villages revealed that each manages roughly 4.5 hectares of cashew monoculture farm alongside 4.7 hectares of agroforestry plots. On-farm inventories of 300 one-hectare agroforestry plots confirmed that cashew accounted for 52% of all trees and was present in 85% of plots. Nearly all interviewed farmers (98%) considered cashew their most profitable crop (Magala, 2025).

In the next section, I discuss five key takeaways from this expansion that can inform and guide the implementation of Nature-based Solutions across Africa.

Lesson 1. International Market Prices Shape Local Practices

Across Africa, farmers are not price makers; they are price takers. The value of their crops depends on world prices transmitted through value chain actors. When international prices rise or fall, local rates follow, and farmers respond by adjusting inputs, expanding or reducing land, or shifting to other crops.

This highlights how rural producers are downstream actors of global economic decisions. Thus, the impacts of local campaigns and awareness efforts on green solutions will likely remain marginal as long as global markets reward yield over ecology.

Lesson 2. Farmers Are More Economists Than Ecologists

Farmers rapidly adopt systems that offer higher returns with less labour. Cotton once dominated northern Côte d’Ivoire, but between 2000 and 2008 its production fell from 400,000 to about 120,000 tonnes, and the number of producers dropped from 180,000 to 72,000. One key reason was that cashew’s net revenues became three times higher than those of cotton (Estur & Gergely, 2010).

Traditional agroforestry systems also declined. In Tengréla and Ouangolodougou near Korhogo, they shrank by 60.8% and 47.22%, largely converted into cashew monocultures between 1990 and 2020 (Timite et al., 2023). Likewise, land once used for food crops has declined, altering consumption habits. In Gontougo, once renowned for its yams, farmers now buy yams with cashew income after converting fields into cashew orchards (Mighty Earth et al., 2023).

This shift reveals farmers’ remarkable adaptability and economic rationality. It indicates that green solutions will remain sidelined unless they generate benefits within farmers’ short- and medium-term horizons.

Lesson 3. Sustainability Fades When the Research-Practice Connection Is Broken

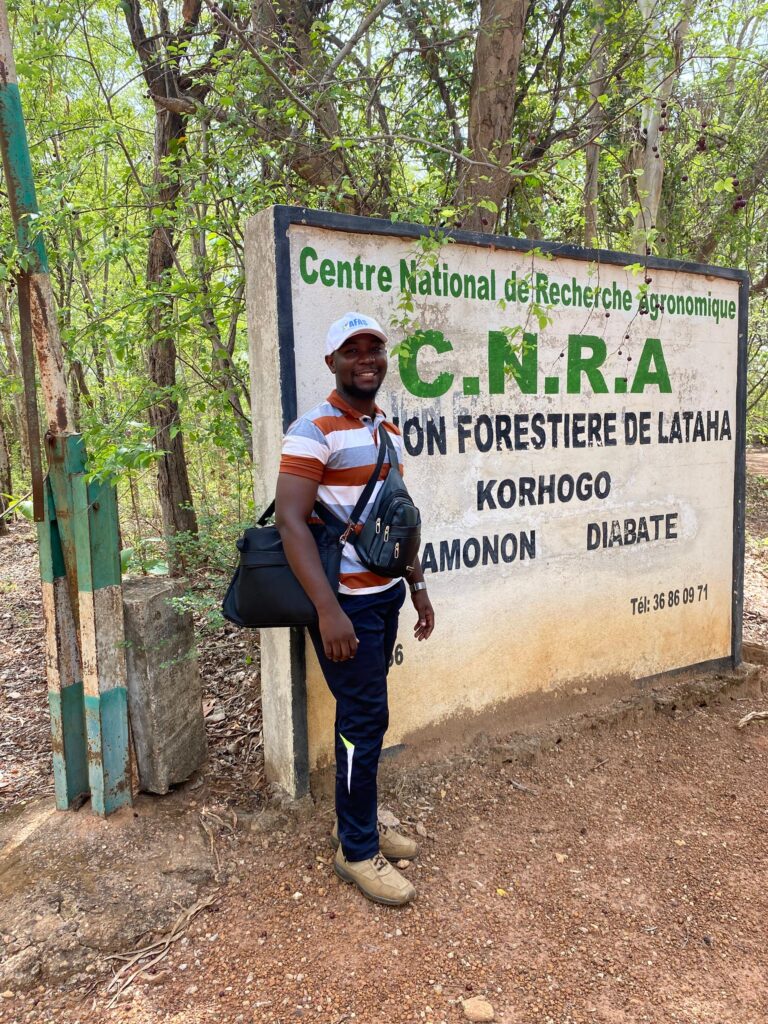

Between 1999 and 2011, promising experiments at the National Center for Agronomic Research (CNRA/Korhogo) were abandoned due to political instability. These included research on live hedges, windbreaks, alley cropping, and the role of trees in crop performance and village economies were abandoned. Although research activities have gradually resumed, they remain limited. This research hiatus left farmers with a narrow set of options, relying largely on extensive monocultures of cashew, cotton, and mango.

When local research slows, adaptive management stalls, extension services weaken, and policy decisions lose their evidence base, jeopardizing long-term sustainability.

Lesson 4. Policies Must Be Proactive, Not Just Reactive

Although cashew was initially promoted by the government as a restoration crop, policy frameworks did not guide its expansion. In the Séguéla region near Korhogo, cashew plantations increased by more than 7,000% in 17 years without a coordinated land-use plan (Bamba, 2019). Even around Comoé National Park (PNC), a UNESCO World Heritage Site, cashew areas increased by 160% between 2002 and 2014, while forest cover declined by 76% (Sangne et al., 2019). Furthermore, 80% of my key informants link this unregulated expansion to growing land conflicts in northern Côte d’Ivoire.

Policies now try to address problems that could have been anticipated. Sustainability in Africa demands research-driven policies that anticipate challenges rather than react to them.

Lesson 5. Caution with Exotic Species

Exotic species often have unintended effects; their introduction should therefore be preceded by thorough, long-term, and multi-scale assessments of their impacts. Recent studies show that cashew roots release chemical compounds that inhibit the growth of nearby plants (Okoronkwo et al., 2024). Farmers expressed this simply: “Under and around cashew, nothing grows.” Additionally, Falk et al. (2025) reported that cashew expansion affects the local water cycle, reducing groundwater recharge and altering evapotranspiration patterns. Similar concerns about exotic acacia species have been documented in the Democratic Republic of Congo and in many other contexts (Wuenschel, 2019). Native species should remain the default choice when designing green solutions.

Conclusion

The half-century expansion of cashew cannot be reduced to a binary assessment of “good” or “bad”. Instead, it provides a vivid case study in the complexities of sustainability. What began as a restoration effort has, through unchecked economic success, led to ecological simplification, intensified land-use conflicts, and the erosion of traditional agroforestry.

The lesson is clear. Ecological intentions are fragile without sustained support. Green solutions alone cannot endure; they must be reinforced through adaptive local research, economic incentives that align farmer livelihoods with long-term ecological health, and agile, forward-looking policies that can steer economic trends, rather than merely react to them. Sustainability, therefore, is not a static goal but a continuous negotiation between ecology, economics, and governance.

References

Information about the author:

Jonathan Bachiseze is an AFAS fellow from the 2nd master cohort based at the Université Félix Houphouët-Boigny in Côte d’Ivoire.

Contact email: a.jonathanbachiseze.m[a]gmail.com